By Carolyn Camilleri, September 20, 2023 in Ground Water Canada

For Christine Burke, the laundry was the first clue she had a problem.

“I kept getting black sludge-like markings on my clothes, and we ended up throwing a lot of clothes away,” she says. “My dishwasher broke down. My washing machine broke down. We changed all plumbing in the house. We changed the holding tank and the hot water tank. We changed the line from the well to the house. This is over a course of a couple years, trying to figure out what was going on.”

Burke has lived in Dover, a community in Chatham-Kent, for 40 years. Her husband was born and raised in the same house. His father, who passed away in November 2019 at age 99, raised all his kids here and ran a farm. The entire time, the property has functioned on well water.

Then, about a decade ago, everything changed. Burke had no idea why, until she attended a meeting held by Water Wells First, a citizens group formed to address concerns about wind turbines.

“We found out that we weren’t alone,” she says. “There were a lot of people impacted by the construction, the pile driving – 100-foot H beams, 25 per turbine and for five turbines. A lot of people lost their water.”

One neighbour had just installed a brand-new, state-of-the-art, stainless steel, four-inch casing well. It ran perfectly until the turbines started operating.

“He is lucky if he can fill a five-gallon pail in five, 10 minutes,” says Burke.

Like many other property owners in the area, Burke installed a type of water treatment operation in her home.

“We’ve got 10 filters, and we have four sediment traps and six cartridge filters on our system,” she says. “But the black shale is so fine that you can’t filter it out. It’s impossible to filter out. I’ve even spoken with the company that provided the filtration systems for the wind industry to give people during the construction when their wells were going down, and they flat out said, ‘We’re sorry. We can’t even filter this stuff out.’”

Instead, they bring home five-gallon jugs of drinking and cooking water.

The effects on groundwater are just one of the problems attributed to these massive structures. Ruby Mekker, who describes herself as an advocate for the protection of people’s health, lists fatigue, tinnitus, heart palpitations, and nausea, plus the many toxic materials used to construct and run the turbines as health issues.

“They’re useless, unreliable, costly, and harmful, but more than that, Ontario has the Health Protection and Promotion Act, and it clearly defines what a health hazard is that has or is likely to have an adverse health effect on the people,” she says. “Why are Ontario laws not being followed? The other one is the Environmental Protection Act. People have a right to live safely in their own homes. And, of course, the nuisance. Why are these other landowners allowed to put something up on their property that impacts people up to 15 kilometres away?”

What makes it all so much worse is the struggle to get people with the power to do something to listen to them and act.

Looking back

This is not a new story. In fact, the contentious situation has been covered in Ground Water Canada several times, including in the summer 2019 issue: “Turbidity and Turbines? Citizens and Scientists seek solutions to water-well issues in Chatham-Kent, Ont.” (https://mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?m=3977&i=595616&p=10&ver=html5) “Excessive sediment, problematic gases, and off-putting, potentially infection-causing biofilm” were found in the well water. It had worsened to the point that well water was unsuitable for bathing, let alone drinking. Farmers were worried about using it on crops for fear it would poison the food. These wells, drawing from a fragile contact aquifer, had been providing the largely rural community of about 100,000 residents with clean, drinkable water for decades.

“Imagine being on one of these rural properties, and you’ve lived there for 20 or 30 years, or in some cases, you’re third generation, and you’ve been using the same water well for three generations and never had a problem,” says Keith Benn, a professional geologist originally from Wallaceburg and residing in Lambton. He is a former University of Ottawa professor and is currently an independent consultant in the minerals industry.

“All of a sudden, they construct these wind turbines a few hundred metres away, and suddenly your domestic water supply is gone,” he says. “You can’t just tap into a municipal water supply. People are paying to have water trucked to their homes. They’ve installed cisterns. It’s a nightmare.”

The heart of the issue for water well owners is the vibration from constructing and operating the wind turbines. Benn says the turbidity of the water is constant for some people, and for others, it tends to wax and wane depending on wind direction and intensity.

“These wind turbines are built on top of pilings that are driven right through the aquifer and into the bedrock. When those wind turbines are operating, they’re necessarily going to send maybe long wavelength vibrations, something like micro-seismic vibrations, into the aquifer,” he says. “And I think those vibrations may well be causing liquefaction of the aquifers, such that the solid part of the aquifer, the gravel, silt, and clay that normally would behave as a solid and just let the water flow through, become liquified, such that those particles then flow with the water and come up the water wells. For some people, like Christine Burke, this seems to happen all the time, every day.”

Over the past decade, the question of whether the turbines are the source of all the problems has been battled back and forth between people and turbine corporations and various government levels. It’s a story rife with plot twists and bureaucracy.

But the most recent developments in Chatham Kent may be slightly hopeful signs that someone will finally pay attention.

They only tested the water!

In 2019, the Ontario Ministry of Health enlisted an expert panel to conduct an all-hazard investigation of water wells in North Kent. Benn was one of the experts invited to be on the panel.

The Ministry of Health then put out an RFP for an independent third-party vendor to collect and test water and sediment samples from private water wells. Both the liquid (water) fraction and the solid (sediment) fraction were officially listed in the RFP as part of the objectives of the investigation.

“This is what was required, and I can assure you that the expert panel was expecting the contractor would capture both the liquid fraction and sediment fraction and analyze them separately for potentially toxic components,” says Benn.

But not one sample of sediment was collected.

“We, on the expert panel, didn’t even become aware that the contractor was not collecting solid fraction or sediment until phase one of the study had been completed, which turned out to be the majority of the sampling,” he says. “By the time we were made aware, it was too late.”

Benn adds that standard techniques used by Ministry of Health for sampling water are not, as a rule, trying to capture the solid fraction. But in this case, the solid fraction was specified in the original RFP.

“I think the ministry should have asked the contractor to correct for that and sample properly, but the ministry didn’t,” he says. “And I should point out something that needs to be stated explicitly: the expert panel that was brought in to advise the all-hazard investigation did not manage any part of the all-hazard investigation. We were brought in as advisers. The Ministry of Health chose the region where the study would be carried out and were the direct managers of the whole thing from start to finish.”

And that is how such investigations should be managed.

Sediment analysis followed by bio-availability testing if metals were found were listed among the expert panel recommendations, which were included with the final investigation results submitted to the Ministry of Health in December 2021.

However, in April 2022, despite the oversight and based only on the analysis of the liquid fraction, the Ministry of Health sent a letter to Chatham-Kent residents indicating that no wide-spread health risks were identified but that testing would continue.

In November 2022, Benn released a review of the all-hazard investigation that further highlighted the sediment-analysis oversight. Because it was, and continues to be, the sediment that people are concerned about – specifically, sediment from the Kettle Point Black Shale geological formation, which represents the bedrock immediately underlying the aquifer, and which is also known to be present as fine grain particles within the aquifer itself.

Residents take action

Disappointed with the outcome of the all-hazard investigation, Burke and other affected well owners banded together to have the sediment tested under the direction of Benn. They fundraised to cover costs and, by the end of January 2023, had about $12,000 – enough to test eight more wells in addition to Burke’s well, which had already been tested. On Feb. 8, the sediment samples were sent to RTI Laboratories in Livonia, Mich. – the same U.S. lab that tested the water in Flint, Mich. Results were returned on April 19, 2023.

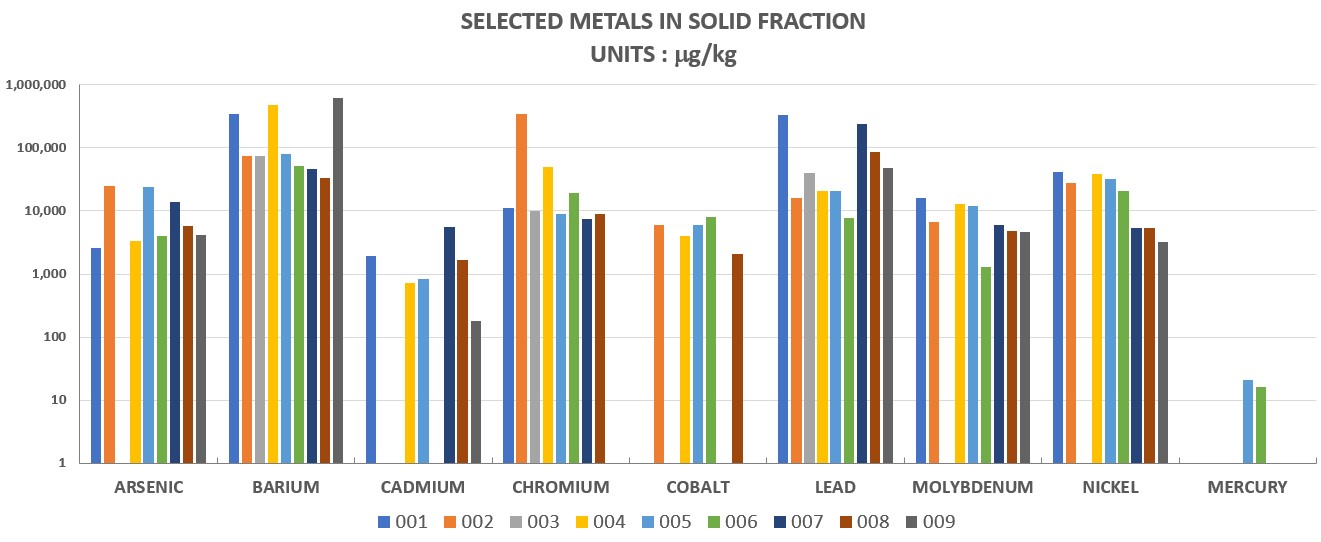

“Each and every sample has metals in the sediment that, if they’re bioavailable, could be toxic – arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, lead, and a couple of them had mercury as well,” says Benn.

They got the verifiable proof they needed – and they got support from the municipality.

On May 15, 2023, Coun. Rhonda Jubenville, Municipality of Chatham-Kent, put forth a motion to request and strongly encourage the Ontario Ministry of Health to do the sediment testing that should have been done during the all-hazard investigation and to follow that with complete studies of bioavailability of potentially toxic substances in the sediment in all water wells in North Kent. Deputations to Chatham-Kent council were made by Benn, Burke, and four others on May 29, 2023. The motion was unanimously approved.

The sequel

As for what’s next, we wait. At the time of writing, the province hadn’t responded yet to the Municipality of Chatham-Kent, but Coun. Jubenville says she is determined to ensure the Ministry of Health is held accountable for sediment testing. Burke wants to feel positive.

“I’m trying to stay optimistic, but I feel like we’re nobodies,” she says. “They don’t care. I just feel like we’re going to get swept under the rug again.”

Benn says it is important to “keep the heat up” and push the Ministry of Health to act.

“I feel fairly confident in saying that the data suggests strongly that the quality of the domestic private water wells in that part of Chatham-Kent has been interfered with – made worse by the construction of that industrial wind complex,” he says. “We know there’s more black shale in the water than there used to be in many cases. Of course, it’s going to vary from well to well. This is part of a complex geological system. And we know there are metals in that sediment that if they’re accessible to the human body, they’re toxic. This has got to be followed up on. This has got to be dealt with.”

For Burke, who has replaced her washing machine and dishwasher yet again, it can’t be dealt with soon enough. She wants safe water and her life back.

“If they were to shut the turbines down, maybe there’s a possibility that the aquifer could repair itself, but I don’t think we’ll ever see that in our lifetime,” she says. “Up the road from us, their water’s pitch black when it comes out of their well. It seriously looks like oil coming out of their well.”

Meanwhile, residents from the 13 homes on Burke’s road signed a petition to get a municipal waterline – and it’s possible, but they are expected to pay for it themselves.

“They took our [well] water away and now they want $47,000 from each household,” says Burke. “And that’s only going by the road. I have a long driveway. It’s probably a thousand feet. Can you imagine how much it would cost me just to get it piped into the house?”

Meanwhile, other wind turbines are being constructed and planned in other places.

“The damage is done here, and that’s why I’m out there warning people,” says Burke, adding that she also communicates with people in the U.S. where wind turbines are going up. “I can’t warn enough people.”

Wind Concerns is a collaboration of citizens of the Lakeland Alberta region against proposed wind turbine projects.